This is an article on uncontrolled IFR in Sweden that I wrote for the Instrument Pilot magazine. (Some details have been revised in November 2022.)

Uncontrolled IFR – the very notion evokes emotions. Depending on what you are used to opinions differ. Some pilots feel it is foolhardy at best and while permitted by EASA regulations, some national authorities attempt to ban it or make it impossible in practise. To other pilots and authorities it is a standard procedure which is even used by airlines. In this article, I’ll describe the procedures and rules for uncontrolled IFR in Sweden.

Why would you want to fly uncontrolled IFR in the first place? If your departure and/or destination airport is uncontrolled, you have to if you want to fly IFR all the way. It can also be for reasons of weather. In the southern third of Sweden (south of 60°N) where approximately 85% of the population lives, terrain is generally flat. The minimum safe IFR altitude is nowhere higher than 3300’ AMSL. By flying uncontrolled IFR at low levels, you can often avoid strong headwinds, convective clouds or flight in icing conditions while still enjoying the advantages of IFR. Particularly being able to fly below the freezing level is a clear advantage as most light aircraft don’t have deicing.

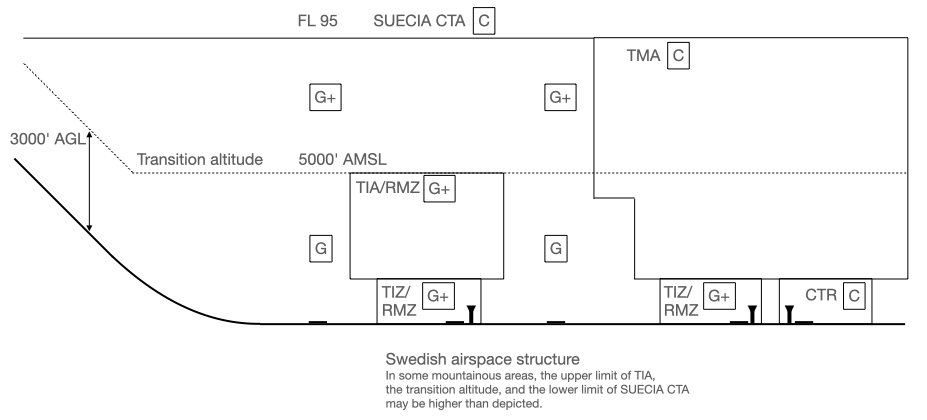

Let’s start with a look at the Swedish airspace structure (figure 1). Above FL95 all airspace up to FL660 is controlled (airspace class C, control area SUECIA CTA) and also all ATS routes have a minimum level of FL100 or higher. As you can see, if you want to fly controlled IFR enroute and don’t have oxygen on board, there is in practise only that single level available. Below FL95 and outside of TMA/CTR all airspace has class G. (In some parts of the Swedish mountains, the floor of SUECIA CTA is FL125.)

However, special rules apply when flying above 5000 ft AMSL (or 3000 ft AGL, if higher) or in a Traffic Information Zone/Area – TIZ/TIA. TIZ/TIA are established around uncontrolled instrument airports to provide a known environment to IFR flights. I’ve used airspace class “G+” for that airspace. (The “G+” designation isn’t officially used in Sweden but it is generally understood to mean class G with added requirements.)

In the “G+” airspace additional rules apply if you fly IFR. You must be on a flight plan, you must have an operating transponder with altitude reporting and you must be in radio contact with ATS. Similar rules apply to night VFR and to day VFR in TIZ/TIA. This means that all traffic with a cruising level above 5000 ft AMSL (or 3000 ft AGL, if higher) will operate in a known environment while in IMC, at night or during takeoff and landing at an instrument airport (at least as long as there is an TWR or AFIS unit in operation – more about that later).

So how is the “G+” airspace managed? In TIZ/TIA, FIS is provided by an AFIS unit at the airport. Enroute, Sweden differs from many other countries in that there is no specialised enroute flight information service. FIS is instead provided – both to VFR and IFR – by the ATC unit responsible for the overlaying controlled airspace. This can be either approach control, if you’re flying below a TMA sector, or enroute control if you’re flying below SUECIA CTA. Generally the same frequency is used for enroute ATC and FIS, although in the southernmost parts of Sweden with a higher intensity of traffic in class G, separate frequencies are used.

The advantage with this arrangement is that uncontrolled IFR traffic can be handled by controllers in much the same way as they handle controlled IFR. ATC will have your flight plan, they will coordinate with adjacent sectors and hand you over in essentially the same way regardless if you are a controlled flight or not. At the beginning of the flight you will get a clearance all the way to your destination which remains valid even if you leave and later re-enter controlled airspace. Changes of level or route in uncontrolled airspace means changing the current flight plan so that should only be done after informing ATC. If you want to climb into controlled airspace, no coordination is required as you’re already talking to the right controller.

The ATC controller or AFIS officer will provide you with information of any known traffic that may be in conflict with you. If you are given a radar service – which is normally the case enroute – the controller may give avoidance advise if (s)he considers it to be warranted. Of course ATC service always has priority over FIS, so there is a theoretical risk that the controller won’t have time to provide FIS. In practise, though, this works very well.

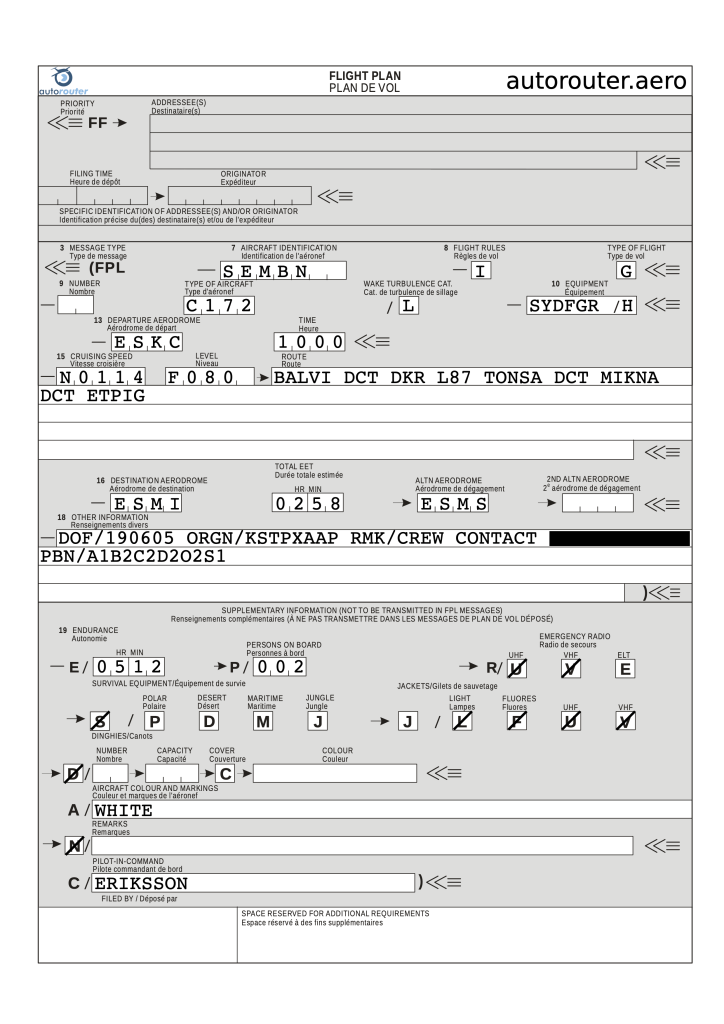

Let’s look at an actual flight that I made in 2019 on a vacation trip to the Adriatic Sea (figure 2). My home field (Sundbro, ESKC) is located inside the control zone of Uppsala airbase, so the flight started out as a controlled flight. You may note that I was on an “I” flight plan even though neither the departure nor destination airports were instrument airports. This is generally permitted in Sweden and simplifies flight planning as you don’t have to specify particular points for flight rule changes. Also, departing a non-instrument airport according to IFR is generally permitted. More about this later

The tower of Uppsala airbase gave me my transponder code and a route clearance to my destination ESMI. The flight was planned at FL80, meaning that it was controlled only within CTR/TMA. Outside of that, I would be flying in the “G+” airspace below SUECIA CTA.

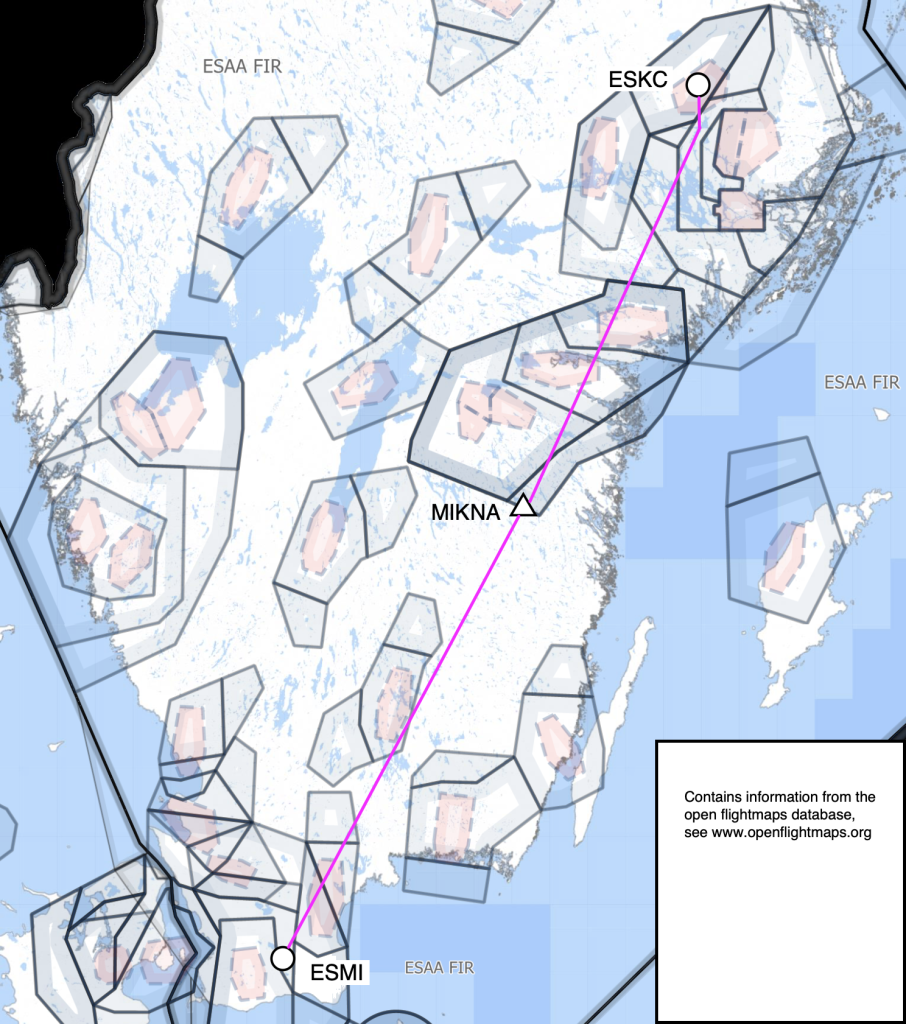

The flight proceeded like any other controlled IFR flight until I left Östgöta TMA at MIKNA and was handed over to the SUECIA CTA enroute controller (figure 3). After calling and stating my level I was greeted with “Identified” and “No traffic reported in uncontrolled airspace” – which is the usual situation at these levels.

Some 70 miles later, I briefly entered Kronoberg TMA. Here the enroute controller coordinates with the approach controller. The approach controller decides if (s)he wants me handed over to the approach frequency or if I can stay on the enroute frequency. In this case, I stayed on the enroute frequency during the very short stretch through the TMA. In any case, no additional clearance to enter the controlled airspace was required as I already had clearance to my destination.

Getting closer to my destination I entered the Kristianstad/Malmö TMA complex. Again, no additional clearance to enter controlled airspace was needed. In this case my destination was a non-instrument airport under the TMA, so I had to leave controlled airspace by descent. This can sometimes be tricky as ATC is not allowed (per ICAO standards) to clear IFR flights below the MVA unless on a STAR or IAP – you have to cancel IFR first. This can lead to unnecessarily high ceiling requirements for the approach as the MVA is generally determined by the floor of controlled airspace and not by obstacles. In this case the MVA was 3000’ while the minimum safe altitude was 1900’. Flying IFR below controlled airspace lower than the MVA is in itself no problem as long as you have obstacle clearance.

As you can see, uncontrolled IFR in Sweden is seamlessly integrated into the ATC system. If you’re not carefully monitoring your progress against charts showing controlled airspace, the only hint that you’re leaving controlled airspace is generally that you’re given traffic information. You may be led to believe that there’s little practical difference between controlled and uncontrolled IFR but that is certainly not the case. If you’re on a controlled flight, ATC will check the status of all restricted or danger areas along your route and route you around them if necessary. Also, unless you’re on an established route, ATC is responsible for your obstacle clearance. None of these are true for an uncontrolled flight. The onus is on the pilot to request permission to cross any restricted areas and to check terrain clearance.

This was made all too clear in 2012 when a C-130J Super Hercules of the Norwegian Air Force crashed into a mountainside in northern Sweden. The aircraft was inbound to Kiruna (ESNQ) airport. ATC gave a “when ready descend” clearance that would take the aircraft out of controlled airspace if the descent started too soon – which was also what happened. The flight crew apparently did not realise that they had left controlled airspace and assumed that ATC took responsibility for terrain clearance. The accident investigation concluded that the accident was caused both by the clearance and by insufficient flight preparation routines within the Norwegian Air Force. After the accident it was clarified that ATC may not give a clearance that can take an aircraft out of controlled airspace unless it is clear that this is the pilot’s intention – either according to the flight plan or by explicit request.

Finally, I’ll say a few words about IFR approaches and departures at uncontrolled airports. If the airport is an instrument airport with an AFIS unit in operation, then things work very much like at a controlled airport – except of course that your flight isn’t controlled and that you have to self-separate from any other traffic using traffic information provided by the AFIS unit. Before departure, the AFIS officer will give you your clearance, relayed from ATC. No vectoring is provided in uncontrolled airspace, so on arrival an instrument approach has to be flown full procedure unless there are charted direct arrivals. An exception is when then airport lies below a TMA, like one of the example uncontrolled airports in figure 1. In that case the approach control for the TMA can vector you to final. That is also the only situation where you need an approach clearance to an uncontrolled airport.

If the airport is not an instrument airport (or it is but the TWR or AFIS unit is closed) procedures are different. You can still take off according to IFR, but you must get your clearance from ATC by radio. There is no way to get a clearance by telephone on the ground before take-off. This means that you may not want to enter IMC before getting the clearance.

On arrival it is up to you to get on ground using whatever procedures are permitted by regulations. You can use an instrument approach procedure at an instrument airport even if there is no TWR or AFIS in operation – although a few airports do not permit this. This possibility has been officially recognised by the Swedish Transport Authority in their circular MFL Ö 1-2022 (In Swedish only.)

If it is not an instrument airport, the regulations allow you to use a let-down procedure of your on making. (Although this is at the present time subject to some debate in Sweden, even though I myself find that part-NCO and SERA are quite clear – particularly after the revision of part-NCO in October 2022.) If the weather is good, of course, you simply fly a VFR approach.

Acknowledgements: I wish to thank Martin Sandback, ATCO at the Stockholm Area Control Centre, for fact-checking the original article. Any remaining errors are, of course, entirely my responsibility.